Book notes from 2018

These are the books I read in 2018 and some brief thoughts they inspired. I don’t consider these reviews, nor summaries—they’re unstructured, my main goal being to preserve the memory of how I felt about them as I read them. Call them personal reflections.

They’re listed in the order in which I finished each book. I’d recommend almost any of these to someone looking for a good book, but my top five favourites are marked with ★

This exercise is chiefly for my own benefit. But should you read them, I hope you find something valuable in my reflections, maybe even a book that interests you—add it to your list in 2019!

- Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

- The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin

- The Technological Society by Jacques Ellul ★

- We Were Eight Years In Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke

- This Census-Taker by China Miéville

- The Business by Iain Banks

- Surprised By Joy by C.S. Lewis

- Confessions by Augustine of Hippo

- The Dry by Jane Harper

- Artemis by Andy Weir

- Gormenghast by Mervyn Peake ★

- Life Together by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

- Art and the Industrial Revolution by Francis D. Klingender

- Terra Nullius by Claire G. Coleman ★

- Writings of the Luddites by Kevin Binfield ★

- Stories of Your Life and Others by Ted Chiang ★

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

On the back of a recent swell of interest in stoic philosophy among the startup and tech communities, I decided to check out one of the classics. I read one of the oldest available translations from Project Gutenberg, which by turns frustrated me with its verbosity and won me over with its occasional beauty.

“The cause of the universe is as it were a strong torrent, it carrieth all away.”

In the end, I found the book more interesting for historical reasons than philosophical ones. There were a few helpful aphorisms to remember, a handful of pieces of advice I decided to try to take on and implement in my own life. But mainly I just found the self-reflections of a Roman emperor, probably the most powerful person alive at the time, to be fascinating.

Marcus Aurelius’s character, if accurately revealed by these writings, seems at once to be the best and worst type of person to be an emperor. He strives to be rational and unemotional, fair and impartial, kind as well as loyal. But he seems self-absorbed, caring only about the development of his own inner response and virtue.

Not knowing anything about his historical reign, from these pages I would imagine him to have no positive vision for the empire he led, no goals other than to carry out the duty of his office simply because he had to. His fixation on the way of nature and the futility of acting against it don’t seem like a good basis for creating any positive change in the world.

While he presents himself as devoid of range and jealousy, he also seems empty of love. In a leader, I can only see this as a flaw.

The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin

I had been looking forward to this book, both as a modern classic and as a work from a non-Western writer. I found myself disappointed by it, sadly.

While the latter half of the book introduces some mind-bendingly large scientific concepts that I enjoyed, I couldn’t get past the sense of nihilism that pervaded the story. From the main character’s seeming lack of emotional response to the events around him, to other characters’ explicit hopelessness, to the creation and destruction of entire universes in the course of scientific experiments, I found the atmosphere bleak.

I do tend to enjoy works that are bleak or melancholy, as long as they have some grounding in characters who I care about, and characters who can have fun and joy even amidst what’s going on in the broader strokes of the narrative. I didn’t find that here.

The creativity and thoughtfulness behind concepts like the atom spun out into a light-seconds-long ribbon tickled my imagination. The same incisive writing created a razor-sharp sense of danger from the antagonists, which must have contributed to my feeling of the story’s bleakness.

I don’t feel like the author’s sheer imagination outweighed my ambivalence towards its characters and my experience of reading it, but I intend to read the next book in the trilogy… so I guess, in the end, does it matter?

The Technological Society by Jacques Ellul

I first heard of Ellul when he was cited in Progress and its Critics by Christopher Lasch. I marked him down as someone interesting—a Christian anarchist? When it came time to pick a book, this one immediately jumped out as being relevant to my interests.

It did not disappoint. I was floored by Ellul’s writing, his commanding knowledge of vast swathes of history, and his insightful theory of technique.

Summarised inadequately, Ellul’s argument is this: the most important factor in the development of modern Western cultures is technique. Technique is the rational maximisation of efficiency in every area of human endeavour. Technique is not concerned with morality, culture, or humanity—only with yield and efficiency, whatever the activity.

Technique is separate from technology, despite the book’s English title:

“The machine is deeply symptomatic: it represents the ideal toward which technique strives. The machine is solely, exclusively, technique; it is pure technique, one might say. For, wherever a technical factor exists, it results, almost inevitably, in mechanization: technique transforms everything it touches into a machine.”

As I worked through the dense chapters, I was regularly amazed by Ellul’s writing, frustrated by his vague citation, terrified that he was making it all up, and on occasion I laughed out loud at his audacity*. But consistently, I felt like I was learning something true, something fundamental about the world. It was putting a name—technique—to a feeling I’d had for a long time.

Working in technology, one often feels that technique, not any humane or ethical factor, is dictating your actions. Even when that is not explicitly stated, the technology industry in general and startups in particular operate under the the assumption of efficiency.

"The human being is no longer in any sense the agent of choice … He is a device for recording effects and results obtained by various techniques. He does not make a choice of complex and, in some way, human motives.

The book inspired me to think differently about technology, and to recognise technique in non-technological areas. It is my favourite book of the year, and I know it will stay with me for the rest of my life.

I hesitate to recommend it unqualified, because it really is an enormous and tedious book. But if you are a technologist who is interested in the interaction between technology and society, I think you should be familiar with Ellul’s ideas.

“The tool enables man to conquer. But, man, dost thou not know there is no more victory which is thy victory? The victory of our days belongs to the tool.”

*The detailed discussion of techniques of magic, in particular, was as illuminating as it was absurd.

We Were Eight Years In Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates

I feel bad for not having a stronger reaction to this book.

It was excellently written; Coates’ combination of memoir, history, social study and reporting was personal, authoritative and engaging. In combination with Scene On Radio’s Seeing White series, which I had listened to late in 2017, it was an eye-opening and devastating lesson on how race works in America.

While the challenges of black Americans aren’t the same as those of Australia’s first people, this book begun my process of learning that would be continued in Terra Nullius, and which I hope to continue further in 2019.

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke

Technically, I only read the latter half of this book in 2018, but it’s hefty enough that I feel justified counting it as a whole book.

After getting fairly bogged down in the middle of the book last year, I picked it up again and started to enjoy it. Aside from the charming prose, the enthralling plot, and the historical asides pitched just shy of Terry Pratchett-style comedy, I was fascinated by Clarke’s approach to magic.

Having grown up playing video games, I’m used to magic being a system. To serve the needs of gameplay, video game magic must be learnable and manipulable. The “magic” in some of Ted Chiang’s excellent short stories is similarly treated as just another type of natural science: it has rules that are discoverable and exploitable. Even some of my favourite magic, the elemental “bending” in the Avatar animated series, is explicitly likened to the martial arts: skills that require improvement, discipline and structured study.

Clarke’s magic seems, by contrast, to resist to any kind of technique that might tame it. It’s mysterious, temperamental, almost anthropomorphic, tied as it is to nature and the fickle Faeries.

The bookish Norrell could have exemplified a scientific approach to the study of magic. But in Clarke’s world, the study of magic through books only makes it tedious, not more understandable.

Strange’s reckless, intuitive approach is no better; it’s just as impenetrable to most people as the years-long study program Norrell sets out. Until, of course, Strange returns it to England to be used by all: theoretical magicians, children, ministers and vagabonds alike.

Neither approach is anything like a rigorous scientific discipline, allowing Clarke’s universe to be truly magical.

This Census-Taker by China Miéville

This novella struck me as a lovely, haunting tone piece, but little more. I’ve been told there is much more depth to it—which I feel I had no means of accessing. Never mind; I always enjoy Miéville’s writing, and I look forward to reading more of him.

The Business by Iain Banks

I approached this book like I would’ve a trashy airport thriller, which was not at all fair of me and did not do it justice. Despite that, I found it thoughtful, witty and sharply-written, as any Banks novel.

I must have been in the mood for more non-fiction, because delving into the world of the Business felt a bit trivial as I was doing it. I liked the book, though I had a feeling that I’d met this character before—possibly in another Banks novel.

I felt like the plot ended just as it was getting started, and that it was a shame… but I got over it pretty quickly.

Surprised By Joy by C.S. Lewis

I found plenty to love in this intimate memoir. I felt a little let-down that I wasn’t able to more personally access Lewis’s process of conversion, but I really appreciated the story of his life until then. After putting the book down, I felt a kind of affinity with the man, and a desire to visit his resting place east of London*.

Besides the beautiful prose, as you’d expect from a man of his time and education, the sharpness of his recollection impressed me. His description of joy touched me, and I recognised it as something I think I’ve felt before, particularly in connection with places. While I don’t count my English heritage as an important part of me, it is definitely imprinted on my identity. I respond strongly to English history and stories, maybe as a result of being brought up on them, and it is in them I think I’ve most often found that joy.

One, from the closing of the Night-climbers of Cambridge, once gave me that feeling. Here is a small part of it.

"So we step out of one era into the next, and as we close the book it must remain closed for thirty years, until that time when the past begins to look longer than the future.

There are others to follow; at this very moment there may be a dozen climbers on the buildings of Cambridge. They do not know each other; they are unlikely to meet. In twos and threes they are out in search of adventure, and in search of themselves. And inadvertently they will find what we found, a love for the buildings and the climbs upon them, a love for the night and the thrill of darkness.

A love for the piece of paper in the street, eddying upwards over the roof of a building, bearing with it the tale of wood-cutters in a Canadian lumber-camp, sunshine and rivers; a love which becomes all-embracing, greater than words can express or reason understand."

*I was in Amsterdam at the time, and planning to visit London soon after, so this wasn’t as impractical as it might sound. Sadly, I didn’t end up getting to Headington.

Confessions by Augustine of Hippo

This is a book I will need to return to. I hope that as I grow in life and faith, I’ll be able to come back to Augustine with a changed perspective and a deeper understanding. But right now I found myself unable to fully appreciate it.

Don’t get me wrong—I enjoyed the book immensely. Augustine’s honesty is striking, and I always experience a sort of wonderful historical vertigo when I’m confronted by the intellect and sheer familiarity of people from a time we think of as primitive.

The theological content went over my head a little, especially arguments with the Manicheans. I revelled in his flights of philosophy, partly because of their audacity, and partly the quality of the writing and translation (F.J. Sheed, as recommended by my favourite tweeter).

What I appreciated most was the final section of the book, where Augustine gives the reader a bit of an overview of where he’s at as of the writing. This sort of lucid personal reflection is something I aspire to, and it’s encouraging to see the humility and self-awareness of this literal saint.

The Dry by Jane Harper

This was a complete page-turner. I’m not even sure why. Maybe the size of the font, or the fluidity of the writing. But for whatever reason, I blazed through it.

It really reminded me of Noise and Animal Kingdom, Australian crime films. The vibe is similar: a depressed, dogged struggle, a second-hand exhaustion that somehow didn’t slow down my read.

Beyond the strong impression of its rural setting, the heat and the drought, I didn’t take much away from the book. The plot was well-told, but ultimately it didn’t capture my imagination. The characters were well-drawn, but I don’t especially feel like spending any more time with them.

Maybe that’s the sort of place, and the sort of people, Harper was writing about.

Artemis by Andy Weir

Unfortunately I have to say this was my biggest disappointment of the year. I enjoyed The Martian, and had heard Andy Weir interviewed about this book and found some of the ideas quite interesting. But the execution just didn’t satisfy me.

I quite liked the substantive world-building behind the book: the currency based on the cost of transport from earth, the technical details of the moon colony’s construction, the brief geopolitical sketches. But I baulked at its delivery: it was pure exposition, and not the good kind.

I’ve already mentioned how I enjoyed the digressions and fairy-tales of Strange & Norrell, and I’m about to express my love of Gormenghast’s excesses. Even Stories Of Your Life And Others has plenty of expository writing, and on one level it’s similar to Weir’s: it’s designed to beam concentrated ideas directly into your brain.

Maybe the protagonist-narrator’s snarky banter just didn’t agree with me, but whatever the reason, I bounced off it hard. Instead of prompting me to think about the ideas, the information dumps felt tedious and poorly-motivated. That said, I read the whole thing on a particularly terrible pair of flights from Europe to Abu Dhabi to Australia, so maybe my irritation was not entirely the fault of the narrator.

I appreciated Weir’s choice of Jazz as a non-male and non-white lead, but the kind of diversity on display is not an exploration of difference. It was more an exploration of hey, this woman of colour and Muslim heritage can have the exact same personality and voice as my last protagonist!

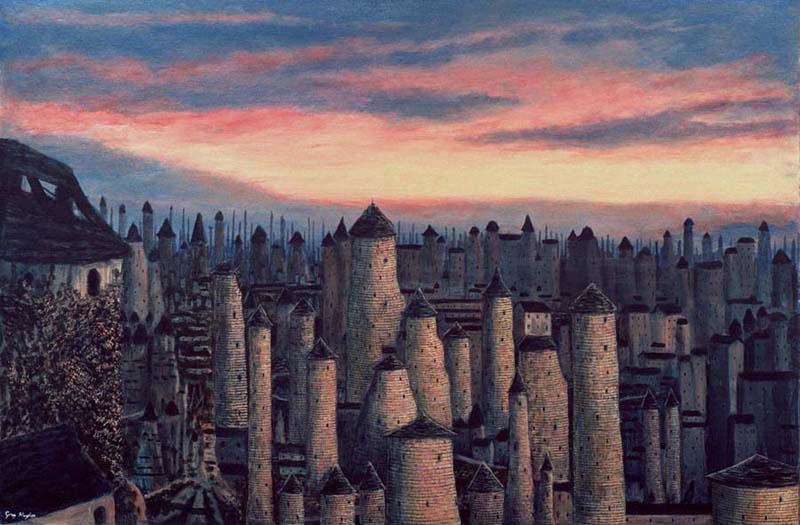

Gormenghast by Mervyn Peake

I am an unashamed fan of maximalist writing. Whether fictional (Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables is one of my favourites) or non (The Technological Society is a great example), I love to indulge in the prose, the journey, the unhurried exploration of places and ideas.

So naturally, I fell in love with Gormenghast from its very first page. Bedizened, cantankerous, excessive but never purple, the opening chapter delighted me with fantastic description, an overbearing but methodical cadence and a sweltering, claustrophobic atmosphere.

“There was a library and it is ashes. Let its long length assemble. Than its stone walls its paper walls are thicker; armoured with learning, with philosophy, with poetry that drifts or dances clamped though it is in midnight. Shielded with flax and calfskin and a cold weight of ink, there broods the ghost of Sepulchrave, the melancholy Earl, seventy-sixth lord of half-light.”

After the opening chapter, featuring metaphorical ghosts and a whirlwind tour of the castle, the action becomes more… straightforward, but Peake never lets slip the precision and creativity of his characterisation and world-building. (I eventually realised that this was in fact the second book of the Gormenghast cycle, which may explain why I was so confused by the opening. I regret nothing.)

The set-pieces Peake constructs are wondrous: from bizarre rituals, through a bitingly hilarious dinner-party to ghastly duels and a truly Biblical flood. I’m firmly convinced there’s more to the book than my experience of it as an aesthetic exercise, but on just that level I was completely engrossed.

I can’t wait to return to this twisted castle, full of grotesque characters and surprising beauty.

Life Together by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Until a friend helpfully pointed out that Bonhoeffer is describing one liturgy, not an absolute standard, I was feeling quite inadequate as a Christian. It’s so conflicting to feel like Bonhoeffer’s vision is truly an ideal, but that it’s almost impossibly demanding, and doesn’t even sound that attractive sometimes!

I was happy that I could take away both inspiration and admonition from the book. I was reminded again that our earthly communities, church especially, will always disappoint us, even as we need them and long for them. But take heart—a Christian community stands on the strength of Christ, not our own individual character. (And if you’re not religiously inclined, Royce argues that loyalty will do the job just as well.)

Art and the Industrial Revolution by Francis D. Klingender

Look, this book mostly went over my head.

I enjoyed seeing some great examples of art from the era, and Klingender’s exploration of the artists and the social environment made them more meaningful.

The history of those times is fascinating and important, but the discussion in this book definitely made me feel like a child privy to an adult discussion. I guess that’s what happens when you pick up a random super-niche book from a shelf in the art history section at Goulds!

I also just enjoyed reading some grating eighteenth-century poetry, a small taste of which I will reproduce for you here:

“Your progress next the wondering muse

Through narrow galleries pursues;

Where earth, the miner’s way to close,

Did once the massy rock oppose.

In vain: his daring axe he heaves,

Towards the black vein a passage cleaves:

Dissevered by the nitrous blast,

The stubborn barrier bursts at last.

Thus, urged by Hunger’s clamorous call,

Incessant Labour conquers all.”

— from “A Descriptive Poem, Addressed to Two Ladies, at their Return from Viewing the Mines, near Whitehaven” by John Dalton (pdf)

Okay, maybe it’s not that bad. Just wait 'til you get to the description of the steam engine.

Terra Nullius by Claire G. Coleman

This is a book I wanted to like more than I actually liked*. I appreciated what Coleman was doing despite its flaws, and I found it effective. If you don’t know about the twist yet, and you want to experience it yourself, please do skip the rest of this section.

Somehow I remained oblivious to the twist until it was explicitly revealed, despite it seeming incredibly obvious in retrospect. Coleman introduces us to an ambiguous setting where “natives” are oppressed horribly by “colonists”. We’re allowed to believe it’s a (somewhat tepid) recreation of colonial Australia, but precisely halfway through it’s revealed to be future Australia. We (humanity) are all the “natives”, and the colonists are grey lizards from another star.

Honestly, I was rolling my eyes throughout the first half. Colonisation bad, yes, I didn’t need to be told again. But as the pivotal epistolary fragment described the destruction of earth’s “natives” by the alien invaders, the persecution and flight of humans into the wilderness, the sorry state of the remaining resistance—allegory so on-the-nose that I had to breathe through my mouth—I felt it.

Damn it, Coleman, you achieved the exact effect you wanted: as the scope of colonial oppression widened to include me, or people like me, I felt it. The effect wasn’t total—it’s not like I had been unsympathetic to the “natives” so far—but it was significant.

Reading Terra Nullius was an important experience for me. I was really challenged to better explore and engage with with Australia’s true heritage. It’s something I’ve always intellectually been on board with (growing up on Midnight Oil will do that to a person), but never pragmatically acted on.

So in the end, while maybe not liking the experience much, I definitely appreciated it. Thank you, Claire.

*To justify that a little more: I thought the writing and characters weren't great. The description in the first half was bland and uninteresting, presumably to keep the twist hidden. The overall plot was tedious. But this is all in small text because in the end, it doesn't matter that much.Writings of the Luddites by Kevin Binfield

Psalters might be the cause of my growing interest in historical radicals. (Have a listen to Diggers All, embedded below, if you want to be similarly inspired. Or if you just want to hear some excellent folk-punk from an inspiring band.) On the back of a couple of articles about the Luddites early in the year, I decided to find out a little more about this much-maligned group of labour agitators.

Writings of the Luddites is a collection of primary source material from Luddites themselves, mostly in the form of threatening letters written to local authorities or businessmen. Stepping back in time to hear the concerns of these men straight from their own mouths was potent. I loved the unexpectedly intellectual discussions of natural rights and political organisation, the frequent references to classics and the Bible, and especially the creative misspellings and typographic layout, heroically preserved by Binfield.

Most uses of the term "Luddite" w.r.t. technology would be more accurate if replaced by "Amish". People don't do that because they are using the term pejoratively and don't want to be seen insulting a group of people who are still alive to take offence.

— Daniel Buckmaster (@crabmusket) November 10, 2018

There’s something powerful about even the meanest and most brutish of these letters—as Green Day put it, this demonstration of our anguish. Binfield does a great job pointing out the motivations behind them, the political and rhetorical concerns that underpin them. Standing bravely in the face of the inevitable march of technique, the Luddites’ lost cause is inspiring.

Here’s one of my favourite letters. It’s not one of the best-written, nor the most historically interesting:

Huddersfield

21 October 1812

RatclifSir,

I drop you this as a warning that I have for some time Eyed you as your Publick character act with so much injustice to almost every individual that has had the misfortune to come before you that I and my two Assocites is this hour your sworn Enimes and all his Magistes forces will not save you, for I dow not regard my own life if I can have reveang of you which I mos ashuredly will make myself another Jhn Bellingham and I have the Pellit mad that shall be wet in you Harts Life Blood if I should dow it in the hous of God

I with hatered your sworn

Enemie AnonimousAdd. Joseph Ratclif Esqr

Millns Bridge

Both assertive and cowardly, at-once vengeful and impotent, the enemie anonimous rebukes the powerful and bears the venom of the downtrodden.

Stories of Your Life and Others by Ted Chiang

I’d been meaning to see Arrival, a film based on one of the short stories in this collection, but never made the time. On a whim, I picked up a copy of this collection (republished as Arrival, with the film’s marketing on it) at a cheap bookshop, not knowing what a gem I’d stumbled upon. After a handful of pages of the first story, I was in love.

While all the stories in this collection gave me something, my particular favourites were Tower of Babylon, Hell is the Absence of God, and Liking What You See: A Documentary. I began to wonder if the author was Jewish given his interest in Biblical themes. They really gave me things to think about as a Christian, as well as just by being interesting and thoughtful stories in their own right.

In a review, John C. Wright called Hell is the Absence of God “trite antichristian propaganda” and suggested that Chiang should “become familiar with (or at least hide his contempt for) the source material” (i.e. the Old Testament).

On the contrary, I think Chiang had far more understanding than Wright game him credit for, as especially demonstrated in e.g. Tower of Babylon. (Is it possible that Wright’s own atheism blinded him to a subtler understanding of Chiang’s use of Christianity?) It’s clear that Chiang makes deliberate departures from a literal reading of Christianity in order to tell a different story using Christian aesthetics and ideas—a little like the astounding animé Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Chiang’s writing really is the science-fiction of ideas, and I was impressed at just how many he could fit in. While it can come across as mechanical, even when exploring pure ideas Chiang never loses sight of the humans in his stories. China Miéville described the writing as having a “humane intelligence”, and I can only agree wholeheartedly.